By John M. Grohol, PsyD

Founder & Editor-in-Chief

According to DJ Jaffe, co-founder of the Treatment Advocacy Center which advocates for mandated outpatient treatment laws, California is “eliminating mental illness treatment.”

According to DJ Jaffe, co-founder of the Treatment Advocacy Center which advocates for mandated outpatient treatment laws, California is “eliminating mental illness treatment.”

This, of course, will be a surprise to the tens of thousands of mental health providers in California. Millions of Californians currently receive treatment for their mental disorders, both in the private and public sector.

In fact, Californians wanted to make up for past deficiencies in funding their mental health services, so they passed a law in 2004 that set aside new money specifically to help fund treatment.

Jaffe claims the money isn’t going to the programs it was intended to fund. Should we take his word for it?

The easiest way to see whether Jaffe’s claims hold up are to look at the text of Proposition 63 itself, the law that Californians passed to increase spending on mental health services in the state. You’ll see in the 7 pages, the Proposition refers repeatedly to things like prevention and early intervention programs (things Jaffe complains about in his article). In fact, in the introduction to the proposed law, the Proposition states:

A recent innovative approach, begun under Assembly Bill 34 in 1999, was recognized in 2003 as a model program by the President’s Commission on Mental Health. This program combines prevention services with a full range of integrated services to treat the whole person, with the goal of self-suf?ciency for those who may have otherwise faced homelessness or dependence on the state for years to come. Other innovations address services to other underserved populations such as traumatized youth and isolated seniors. These successful programs, including prevention, emphasize client-centered, family focused and community-based services that are culturally and linguistically competent and are provided in an integrated services system.

Suddenly, some of the programs Jaffe calls out in his article, such as developmentally challenged youth reading below grade level and giving troubled youth access to proven Wilderness programs seems right in line with what one might expect from the Proposition. It’s all right there, in stunning detail, in the Proposition itself.

But I think the primary confusion and distress by Jaffe comes because his definition of “severe mental illness” doesn’t jive with the State’s. This is not surprising, given that “severe mental illness” has no agreed-upon definition.

Historically, mental health professionals, social scientists and researchers consider “severity” of a disorder on a Likert-like scale for most mental disorders. For instance, you can have a Major Depressive Episode that is categorized as Mild, Moderate, Severe without Psychotic Features, or Severe with Psychotic Features.

Nowhere in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV, the reference guide professionals and researchers use to classify and diagnose mental disorders) is a distinction made whether one type of mental disorder is more serious (or “severe”) than another. ADHD can be just as serious and debilitating to a person as schizophrenia can, and obsessive-compulsive disorder can be just as serious and debilitating to a person as bipolar disorder can. The DSM doesn’t make a distinction.

Researchers, advocacy organizations around the world, governments and professionals don’t have an agreed-upon definition of what constitutes a “severe mental illness” (SMI). The definition of SMI varies widely.

Rethink, a UK charity, suggests psychosis is the defining characteristic of a “severe mental illness:”

There is no universal understanding of what severe mental illness is, because it tends to be seen differently by the person experiencing it, their family and friends and doctors. The term usually refers to illnesses where psychosis occurs. Psychosis describes the loss of reality a person experiences so that they stop seeing and responding appropriately to the world they are used to.

The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) disagrees, and suggests that “serious mental illnesses” include even personality disorders:

[…] major depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), panic disorder, post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and borderline personality disorder.

The National Survey on Drug Use and Health, a U.S. government-sponsored project, defines “serious mental illness” even more broadly:

A mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder (excluding developmental and substance use disorders) Diagnosable currently or within the past year Of sufficient duration to meet diagnostic criteria specified within the 4th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) Resulting in serious functional impairment, which substantially interferes with or limits one or more major life activities

(Point 4 is redundant, since that is nearly always a requirement for a diagnosis to be given from the DSM-IV.)

The Center for Mental Health Services (a U.S. government agency under SAMHSA) defines severe mental illness (SMI) as:

[…] any psychiatric disorder present during the past year that seriously interfered with one or more aspects of a person’s daily life.

DJ Jaffe’s old organization, the Treatment Advocacy Center, doesn’t even define the term anywhere on its website. But they are certain that “[s]evere mental illness is a debilitating brain disease with devastating consequences for individuals who suffer from it, their families and society as a whole.” Brain disease? Really??

Now you can see why Jaffe is upset. He likely only considers a small handful of disorders to meet his definition for severe mental illness, such as schizophrenia and perhaps bipolar disorder. He believes that the other dozens of disorders listed in the DSM-IV are simply not worthy of anyone’s focus or funding.

I disagree. I think Proposition 63 funding is being used exactly as intended. In children, this means things like:

(d) The program shall emphasize strategies to reduce the following negative outcomes that may result from untreated mental illness:

(1) Suicide.

(2) Incarcerations.

(3) School failure or dropout.

(4) Unemployment.

(5) Prolonged suffering.

(6) Homelessness.

(7) Removal of children from their homes.

It’s all right there in the Proposition itself, so none of what the money is actually funding should come as a surprise to anyone who’s bothered to read the law.

So what’s happened to the money the law has generated? It’s going to a wide range of hundreds of programs and services in each county in California that help children, adults and seniors who have mental disorders. Exactly as was intended.

Read DJ Jaffe’s full article: California Eliminating Mental Illness Treatment

In the side rant about Laura’s Law, the so-called “assisted outpatient treatment” law in California, Jaffe decries the lack of adoption of the law across the state (it must be adopted individually by counties).

I might suggest that mandated treatment laws are simply not the will of the people of California. Perhaps they, like me, are wary of returning to the age when a person can’t refuse treatment even when they are not an immediate danger to themselves or others (you don’t have to be in order to be committed under Laura’s Law).

I’m all for helping people who need help, but not at the risk of any citizen’s basic civil liberties. We let go of strong commitment laws decades ago because the government and professionals clearly demonstrated they did not have the ability to uphold and apply these well-meaning laws. Even in many states where the new mandated treatment laws have passed, there is only lip service paid to checks and balances of a citizen’s Constitutional rights.

Dr. John Grohol is the CEO and founder of Psych Central. He has been writing about online behavior, mental health and psychology issues, and the intersection of technology and psychology since 1992. Dr. Grohol also sits on the editorial board of the journal Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking and is a founding board member of the Society for Participatory Medicine.

You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Last reviewed: By John M. Grohol, Psy.D. on 31 Aug 2011

Published on PsychCentral.com. All rights reserved.

APA Reference Grohol, J. Is California Eliminating Mental Illness Treatment?. Psych Central. Retrieved on September 1, 2011, from

http://psychcentral.com/blog/archives/2011/08/31/is-california-eliminating-mental-illness-treatment/

View the original article here

Online Psychology

Image: Getty Images

Image: Getty Images

Image:

Image:  Making a pact with your spouse to work out together may inspire you at first, but you could end up slacking off, relying on his or her nudge of encouragement to get moving. Image: Anthony Nagelmann Getty Images

Making a pact with your spouse to work out together may inspire you at first, but you could end up slacking off, relying on his or her nudge of encouragement to get moving. Image: Anthony Nagelmann Getty Images  Image:

Image:  According to DJ Jaffe, co-founder of the Treatment Advocacy Center which advocates for mandated outpatient treatment laws, California is “eliminating mental illness treatment.”

According to DJ Jaffe, co-founder of the Treatment Advocacy Center which advocates for mandated outpatient treatment laws, California is “eliminating mental illness treatment.” Dr. John Grohol is the CEO and founder of Psych Central. He has been writing about online behavior, mental health and psychology issues, and the intersection of technology and psychology since 1992. Dr. Grohol also sits on the editorial board of the journal Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking and is a founding board member of the Society for Participatory Medicine.

Dr. John Grohol is the CEO and founder of Psych Central. He has been writing about online behavior, mental health and psychology issues, and the intersection of technology and psychology since 1992. Dr. Grohol also sits on the editorial board of the journal Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking and is a founding board member of the Society for Participatory Medicine. In a recent survey of the U.S. population, researchers Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris assessed common beliefs about memory. They found that common beliefs are often incongruent with scientific findings. Recently I had an opportunity to ask Simons about some of the implications of the survey.

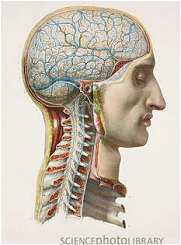

In a recent survey of the U.S. population, researchers Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris assessed common beliefs about memory. They found that common beliefs are often incongruent with scientific findings. Recently I had an opportunity to ask Simons about some of the implications of the survey. Our brains do a lot of work behind the scenes to help us function and thrive. But we largely know this already.

Our brains do a lot of work behind the scenes to help us function and thrive. But we largely know this already. Margarita Tartakovsky, M.S. is an Associate Editor at Psych Central and blogs regularly about eating and self-image issues on her own blog,

Margarita Tartakovsky, M.S. is an Associate Editor at Psych Central and blogs regularly about eating and self-image issues on her own blog,